Docent Training Materials

Passport - Changing World

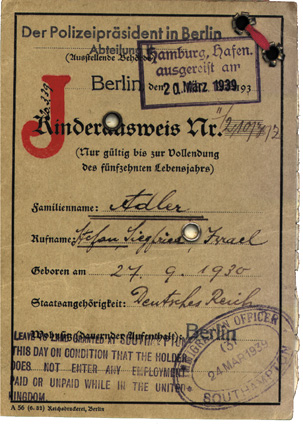

PASSPORT FOR STEPHEN ADLER

This passport was issued in 1939 in Germany.

Notice the large red “J”. This letter was printed on all German Jewish passports

A law was passed in Germany stating that beginning on January 1, 1939, all Jewish men must

take the middle name “Israel” and all Jewish women must take the middle name “Sara.”

In November 1938, the Germans initiated a violent pogrom during which they burned all the synagogues, looted thousands of stores owned by Jewish merchants and arrested 30,000 Jewish men. My Dad was one of the men arrested. He was taken to Sachsenhausen, a concentration camp in Germany, not far from Berlin, for six weeks.

After his release in late December, my parents began arranging for my brother’s and my emigration. My parents submitted applications for both of us to go on the Kindertransport to England. My application was selected, but my brother’s was not. In March of 1939, my parents took me to a train station in Berlin for the trip to Hamburg. From there, I boarded a ship to Southampton, England, along with hundreds of other Jewish boys and girls. I didn’t know then whether I would see my family again….

In England I lived in a small house with a new family. I slept in an unheated attic room. In the spring of 1940, I was reunited with my brother, and that summer we met our mother and father again before traveling by ship to the United States in November 1940.

Stephen Adler, born in Berlin, Germany in 1930, was part of the Kindertransport. Stephen was one of the lucky few – most children who were saved by the Kindertransport program became orphans. Their parents did not survive the Holocaust. Stephen is a member of the Holocaust Center for Humanity’s Speakers Bureau.

Additional Resources

Glossary of Holocaust Terms

Children’s Transport. As the situation for the Jewish people worsened in Eastern Europe, Great Britain agreed to allow 10,000 Jewish children from Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia to immigrate to England. Private citizens or organizations had to guarantee to pay for each child’s care, education, and eventual emigration from Britain. Parents or guardians could not accompany the children. (USHMM).

Click Here for more information.

The Nuremberg Laws also determined who was a Mischling, or part-Jew. Two Jewish grandparents made you a first degree Mischling, whilst one Jewish grandparent resulted in a second degree categorization. These definitions meant that over 1.5 million people in Germany were considered either full Jews or Mischlinge in 1935 – approximately 2.3 per cent of the population. Many people who had never practised Judaism and who considered themselves ethnically German were now declared members of a supposedly inferior, non-German racial group.

On 15 September 1935, the Nuremberg Race Laws were instituted in Nazi Germany. Since Hitler’s rise to power in early 1933, Jews in German society had been subjected to increasingly discriminatory legislation, which mainly restricted their public rights. The Nuremberg Laws, however, went further still in alienating the Jewish population from mainstream society. and even dictated on private matters such as relationships.

Click Here for more information.

From the Russian word for “devastation”; an unprovoked attack or series of attacks upon a Jewish Community (Jewish Virtual Library).

Click Here for more information.

The Theresienstadt "camp-ghetto" was located just 7 miles from Prague. It existed for three and a half years, between November 24, 1941 and May 9, 1945. Neither a "ghetto" as such nor strictly a concentration camp, Theresienstadt served as a “settlement,” an assembly camp, and a concentration camp, and thus had recognizable features of both ghettos and concentration camps.

Click Here for more information.

Population: Of the approximately 140,000 Jews transferred to Theresienstadt, nearly 90,000 were deported to points further east and almost certain death. Roughly 33,000 died in Theresienstadt itself.

Child survivors: 15,000 children passed through Theresienstadt. Although forbidden to do so, they attended school. They painted pictures, wrote poetry, and otherwise tried to maintain a vestige of normalcy. Approximately 90 percent of these children perished in death camps.

Used as Transit Camp: Transports also left Theresienstadt directly for the extermination camps of Auschwitz, Majdanek, and Treblinka.

Click Here for more information.

Red Cross Visit: Germans permitted representatives from the Danish Red Cross and the International Red Cross to visit in June 1944. It was all an elaborate hoax. The Germans intensified deportations from the ghetto shortly before the visit, and the ghetto itself was "beautified." Gardens were planted, houses painted, and barracks renovated. The Nazis staged social and cultural events for the visiting dignitaries. Once the visit was over, the Germans resumed deportations from Theresienstadt, which did not end until October 1944.

Click Here for more information.

Class Photo - Changing World

Frieda Soury

“I grew up celebrating Passover and Christmas. I knew I was Jewish but religion was not a central part of my life. When Germany invaded Czechoslovakia, my religion came to define me.” – Frieda Soury

In 1943, at the age of 14, Frieda was deported to Theresienstadt, a concentration camp in her native country of Czechoslovakia. Frieda was designated a “mischling,” meaning half-Jewish: Frieda’s mother was not Jewish, but her father was. Frieda was assigned to a room with more than 20 other girls. She remembers that the Jewish girls in her room came and went (later she learned they were deported to Auschwitz or other camps) while she and the other mischling stayed as inmates. Frieda worked on the camp’s farm, planting, tilling, harvesting, and moving rocks. While back-breaking labor, this afforded her the opportunity to occasionally steal an extra piece of food. Of the 140,000 people sent to Theresienstadt, 15,000 were children, and only 1,500 of these children survived the war.

Theresienstadt was liberated by the Russians in May 1945. Upon being freed, Frieda’s father acquired transportation for his family and other children from the same hometown and brought them all back to Ostrava. When she was 18, Frieda went to Israel where she met her husband Aaron. They had three children and then immigrated to the United States. Frieda is a member of the Holocaust Center’s speakers bureau.

This is Frieda’s 1940/1941 school photo. Frieda is standing just to the left of the instructor in the middle of the photo. She is wearing a white shirt.

You might notice that all of the students and the instructor are wearing Jewish stars sewn onto their clothing. This was a Jewish school. After the Nazis occupied Czechoslovakia, Jewish students were no longer allowed to attend public schools.

Some of the people in the photo are cut out. After Czechoslovakia was liberated from Nazi control, Frieda found that only a couple of her former classmates survived. These survivors had nothing left: no photos o themselves as children, their families or their friends. Frieda cut their pictures out of this photo to give to them.

Additional Resources:

Frieda Soury's Video Testimony

Red Cross visit to Theresienstadt

Kurt Rosenberg Biography, Part 2

By Jan Jaben-Elion, first published in the Leica Historical Society of the Uk magazine.

Kurt Rosenberg, and other German Jews saved by the Wetzlar-based Leitz company, walked a delicate balancing act in the United States. To some, they were Germans, working for a Germany company in a country that went to war against Germany in 1941. He worked, and owed his life to, a Germany company that was supplying equipment to the Luftwaffe, run by a government that was threatening his family’s life in Germany. He loved his work, and excelled at it, but also felt torn, worrying about his family back home.

In his letters, dating from his arrival in America in 1938 to the time he went overseas with the US Army and was subsequently killed in 1944, we see his concerns for his family and his efforts to get them out of Germany. Yet, we also see a maturing young man who took his work and his love for photography extremely serious. In this second of a series of articles about Rosenberg (the first was published in LHS No. 62, June 2001), we will see a snapshot of what it was like to work for Leitz in America in those early war years from someone who loved his work.

Indeed, not long after his February 1938 arrival in America, he wrote home about the Leica he was building for himself, and his disappointment about how he wasn’t being appreciated by the company. One of his colleagues traveled to a customer for four days to repair a metal microscope. Apparently the lens was foggy (beschlagen) and the machine had to be adjusted. “Why didn’t they send me since this is exactly what I just learned in Wetzlar?” He complained that some of the people in the front showroom had as much knowledge of a Leica as a cow has knowledge about a kreplach (crepe)!

He also wrote about his working in his darkroom from 8 a.m. to 9 p.m. one Sunday, and complained about the heat. “One has to be extremely careful about the temperature of the developer and the fixer. It should have consistent temperature of 18 degrees Centigrade, which is only possible with consistent refilling of ice. In the shop, three of the films melted.”

Six months later, in the dead of a New York winter, Rosenberg wrote about one of his more fun experiences. Julius Huisgen, a photographer commissioned by Wetzlar, came to New York to take color photos of Broadway for a book. “Jule asked me to go with him because four eyes are better and my mouth speaks better (English). We were at Times Square, always looking for a good photo, when I suddenly had an idea: We hired a taxi and took photos from the roof of the taxi. That was the best viewpoint. From there we shot everything again. In all, we took 54 pictures. And the expense I had was reimbursed by the company.”

One day, Rosenberg’s boss, Mr. Schenk, called him into his tiny cubicle office and told him that someone had complained that he had been absent from work for a few hours the previous November, when he was obtaining affidavits to bring his family from Germany, and the time had not been deducted from his pay. “It hurts me, not the few dollars that will be deducted from my next week’s salary, but the last sentence in this meeting was important: ‘I hope I can reimburse those hours.’ This was the first time Mr. Schenk spoke to me for many months. He’s forever going around me and watches how I work. He goes through my drawers after I leave work. This, he told me. So I don’t know where I stand with him.”

One of the biggest news stories involving Leitz during those times – about a theft of thousands of dollars worth of cameras - also was noted by Rosenberg to his family. In May 1939, he wrote to his father that the investigation had not advanced much, but that “a few more people were arrested and one of them from a transport service who had four cameras in his home.” Meanwhile, Rosenberg had transferred to the San Francisco office where he worked for Spindler. One day, Spindler informed him that his former boss Schenk, had been responsible for the theft of $30,000 worth of cameras and lenses. Rosenberg was shocked. “Fourteen years in the company, with a weekly income of $100. Formerly a German officer, a man of 60 years with a little girl of 10 years. He took the cameras home and his wife sold them. Both are now sitting (in the infamous NY prison) Sing Sing. He must have been a first-grade actor when I think about how upset he got when the first three suspects were taken, and how long it took the authorities to catch up with him. Probably one of those who was arrested did not keep his mouth shut. I can’t grasp this.”

Between the theft in the New York office and the recent accidental death of renowned photographer Anton F. Baumann, Rosenberg was very happy to be in the San Francisco office. “I can think of no better employer than Spindler. He kept his promise and is leaving me totally alone to do my experiments.”

During the next two years, while life was deteriorating for his family in Germany, Rosenberg’s creative life with Leitz was flourishing. In March 1940, he wrote about the new simplified Selectroslide and the projector, for which he had an idea: Just like other instruments, theirs were painted in matt-black. A double vent evacuated the heat that is produced by a 300-500 Watt bulb. Still, there was a lot of heat. He suggested to Spindler that they could “get a lower heating and higher light intensity through a silver coating inside. We are sending 20 out to be lacquered and I am very tense. Why don’t other companies do this; maybe it’s wrong? But it makes so much sense to me that a silver coating keeps the heat away and reflects the light, and conversely, a black plane absorbs the light and collects the heat without letting it go.”

Not much later, he reported that his idea turned out to be good and that “the prototype is ready and we can begin producing. It is unbelievable that after two hours, our projector is only as warm as the one from the factory after 10 minutes! It is also lighter, brighter and cheaper! Spindler invented another little thing with which to hold negatives stronger; nothing special, but we make money with it!”

Still, not everything was rosy. Rosenberg wrote that although the new Electroslide was ready, Spindler couldn’t proceed because “we are not allowed to compete against New York.”

But just weeks later, in May 1940, Rosenberg wrote: “The awaited success with the Electroslide Junior has arrived. We have hundreds of orders, but they can only be delivered in four to five months. First of all, the molds for all the necessary parts must be made. This is keeping us back. We have expanded, received new machines, hired 10 people and are still busy. Spindler half apologized that he cannot give us a raise, but as soon as the first instruments are delivered, he will make it up to us. He really now has only expenses and no income. New York’s business is exploding. Almost everything is produced there and they hired 30 additional technicians. Almost daily there are telephone communications with Europe. The prices remained the same, but the profit is naturally much greater because there are no customs to pay and everything goes into their own pocket.”

1941 was a big year in Rosenberg’s life. His father was deported to a concentration camp in Germany. Rosenberg enlisted in the U.S. Army, and he invented something else for photographers. In a letter he wrote to a friend, asking for advice, it is apparent that Rosenberg is now more at home in America. His letter, written in German as usual, is interspersed with English words (here, italicized). He writes, “I have the following idea: A simple box with a short handle and a [Randelschraube] attached to the enlarger’s column. I am enclosing a little sketch for you to be able to visualize it. The whole thing is not supposed to be an invention, but on the other hand, I think that it is very practical. When the amateur works in his darkroom, he wants to have all his instruments handy. Additional lenses, filters, softening lenses, enlarging glass, light meter, etc., etc. When one begins to work, everything is nicely displayed on the table and when one is done, everything is nicely stashed under the table. You see in a darkroom where it is almost completely dark, instruments can never be too accessible. And the little light that is available is most intensive near the enlarger itself.

“Have you understood me so far? The only accessory that comes close to my idea is a drawer that fits under the enlarger’s board. This tool is delivered from the plant just like this and cannot be used with any other enlarger. Then there is another idea. The enlarger’s board here is hollow and has room to stash a few things. But there is nothing that can be used with every enlarger. My ‘tablet’ can remain permanently hinged to the enlarger’s upright, i.e., one has all the necessary things together with the enlarger. Another advantage, the production cost need not be higher than one cent. Each column can accommodate three to four of these holders and thus save a lot of space.

“I am coming to the point (of the letter). I approached the Snow Company in Washington and presented my idea to them. I paid $5 and had them make a search. The result is that there are already four patents that are similar to my idea. I find the letter from Snow very respectful, and it shows that they have not taken me for a ride. (Sorry – what German!) But I cannot grasp that these advanced patents come so close to my thought. I am asking for your professional advice and decision. I am not absolutely eager to get a patent, and not at all if later I might have to face claims by another inventor. Should I try to get a design patent? I enclose my correspondence with Snow. Does he have a good reputation for a patent lawyer?”

Later that year, Rosenberg wrote to his family about how Spindler contacted the US Army to get a deferred classification for him. In this communication to the Army, Spindler noted that the company is the only one of its kind on the West Coast that provides its special services to both private industry and the US government. The letter points out the “current shortage of new scientific instruments and equipment” and the need to keep its “repair department” operating. “Therefore, we require the constant service of Kurt Rosenberg which is unique in that he was trained in the (headquarters) factory and whom we brought over to the West Coast several years ago and at our own cost. Even in normal times it is practically impossible to find such unique technicians in the open labor market.”

Finally, this German-born photographer with an American inventive spirit was inducted into the US Army in April 1943, months before receiving his American certificate of naturalization that October. Thus, still a German citizen when he was first inducted into the army, he was bound by a night curfew imposed on Germans. He was then killed in action in April 1944 aboard the U.S. troopship ‘Liberty Paul Hamilton’, when it was torpedoed in the Mediterranean Sea by German aircraft. Only his letters, full of his creative ideas and spirit, and his many photographs are left behind.

Kurt Rosenberg Biography, Part 1

By Jan Jaben-Elion, first published in the Leica Historical Society of the UK magazine

When German aircraft dropped their torpedoes on the American troopship, “Liberty Paul Hamilton,” approximately 30 miles off the coast of Cape Bengut, April 20, 1944, at least one of the 504 US Army Personnel aboard killed in the immediate explosion and subsequent sinking in the Mediterranean Sea was a brand new American citizen. In fact, he was a German-born Jew who had fled Nazi Germany in 1938. But Cpl. Kurt J. Rosenberg was much more than an unlucky Jewish refugee in the 32nd Photo Ren. Sq. The 5-foot, 7-inch, 154-pound, 28 year old was one of a number of Jewish employees of Leitz, based in Wetzlar, Germany, that was brought by the company to the United States during in the late 1930s.

Indeed, Leitz saved the lives of many German Jews, paying for their immigration to the United States, helping them with the required paperwork, and most importantly, providing them with jobs immediately upon entry. Kurt Rosenberg is only one of these Leitz employees. But Kurt Rosenberg – despite having tragically died as a young man before all of his potential and talents could be realized – left behind hundreds of letters that he wrote and received, original German and US documents, and hundreds of negatives that he took in Germany and America. The actual details of how the company was able to save its Jewish employees, in fact, only came to light in Kurt Rosenberg’s correspondence!

This is Kurt Rosenberg’s story, told through that rich material that he left behind, as well as some of the untold story about the Leitz company in the 1930s and 1940s.

When Kurt was born in Goettingen, Germany, in January 1916, the second son of a Prussian officer who would receive the revered Iron Cross medal, World War I was raging. Two and one-half years later, the German military collapsed. Germany was defeated. Although the semi-autonomous regime of the Second Reich was replaced in 1919 by a parliamentary democracy, Weimar, this was also the same year that the National Socialist German Workers’, or Nazi, Party was created by Austrian-born Adolph Hitler.

Life was hard for most everyone in those dark, depressive days in Germany. Kurt’s mother, Rosel, later wrote that those difficulties were even worse than what she experienced in the late 1930s, before her death due to illness, in early 1939. Still, at least she bore a twin brother and sister in 1921, and her husband Georg had a good job at a Giessen bank, until his forced retirement in July 1934.

Georg was a strong, authoritative husband and father who was quite proud of his service in the German army, and even as the dark clouds of Hitler’s Germany gathered around the family, he believed that his Iron Cross medal of honor would protect him and his family, despite the fact that they were Jewish. When first his eldest son, Hermann, followed by Kurt, talked about emigrating, he was adamantly against it. He saw no need for them to leave the Fatherland. Finally, in 1937, at age 21, when he no longer needed his father’s consent, Herman left for the U.S., where Georg’s brother, Gustav, had been living since the 1920s. Kurt started his emigration process as soon as he, too, reached 21.

Kurt’s emigration was facilitated by the Leitz company. His love affair with Leitz started at the age of 16 when his father enrolled him for a four-year apprenticeship at the main Leitz plant in Wetzlar, starting April 25, 1933. Kurt had an incredible track record with the Wetzlar-based company. As early as November 1935, Kurt writes about the compliments he received for his work, and about his pay-raises. He even invented a Fixed Focus Attachment for the Leica, which, upon his arrival in America, he patented (No. 33130). In 1937, he had a photo exhibit in Frankfurt. Later that year, although he writes that the company agreed to pay all his immigration expenses, he tried to delay his long sought-after travel plans, but that delay was denied. In early 1938, before his departure date, Kurt visited all his friends in Wetzlar to say goodbye. It could not have been an easy “Aufwiedersehen”: He loved his work and he seemed to be well liked. How does a young man leave his friends, his family, the work he loves and his country to immigrate to a place he’d never even visited?

Hitler’s Nazis helped. During the time that Kurt was learning and training for his craft, Germany annexed the Saar region and entered the Rhineland. The Reichstag passed the anti-Semitic “Nuremberg Laws.” Jews had already been dismissed from civil service and denied admission to the bar. Jewish books had been publicly burned. Hitler signed agreements with Italy and Japan, and in the summer of 1937, the Buchenwald concentration camp was opened, although this wasn’t reported at the time. What had seemed like a bright future for this budding photographer in his homeland, increasingly dimmed, until he realized he had to build his future elsewhere.

At the end of January 1938, Kurt left for America, crossing the Atlantic Ocean aboard the Hansa, arriving in New York on an early February morning. The night before his arrival, “I was the last to crawl into bed, as I knew that I wouldn’t be able to sleep. At 5 a.m. Saturday morning, I was on the deck and I didn’t need to regret getting up so early,” Kurt wrote home to his family in Frankfurt, Feb. 20, 1938. “The boat was sailing at half-power into the New York harbor, right and left thousands of lights and in front of us the skyscrapers of Manhattan. It was a quite fabulous view, and I was sorry that it was still too dark for taking pictures.”

Arriving on Lincoln’s Birthday, Kurt had immigration problems and was not at first allowed to disembark. Quickly, he gave to his fellow Leitz refugee, Paul Rosenthal, all his valuables: “my Leitz papers, my ring and everything else that they could have charged me duty for. Then I was called to customs. Five people were going through my things and they were especially meticulous with my photographic equipment. I had to pay a total of $4 in duties. When they asked me how long I had had the camera and I answered, ‘one and one-half years’, one customs officer said in German: ‘The old song.’” Eventually, everything was straightened out, but Kurt, the budding writer, wrote his family that the experience could be entitled, “Immigration with Obstacles.”

Kurt was met in New York by friends who helped him find a place to live, and in general, showed him hospitality. He was invited to dinner at friends in the Jamaica neighborhood of Brooklyn, N.Y. “As I got off the subway, I nearly fell down: a suburb like Wetzlar – peaceful, rather small one-family homes, trees and gardens. I hadn’t thought that there is such a place ‘only’ 25 km. away from New York, for 5 cents and a 30-minute ride on the subway.”

The following day, Kurt showed up for work. Later that day, immigration called looking for him. They noted that both he and his friend Paul Rosenthal who had met him on board, worked for Leitz. “Since not only my fate but also that of the company was on the line,” and the company was afraid it wouldn’t be able to get any more people from Wetzlar, “I was asked by the deputy director, to go to San Francisco, to the company branch there, eventually working there for four weeks and then ask through that branch for a job in New York.”

Kurt’s letters are filled with his homesickness and loneliness in a new country, as well as news to his family back in Germany, relating information about several people from Leica. Indeed, in addition to fellow refugees, Kurt found an extended “family” in his Leica colleagues. He also kept his family up-to-date on what he was learning at work. On the back of one of his self-portraits that he sent to his older brother, he wrote: “…my instructor says that the light over the shoulder is very European and I should get rid of it.”

Interestingly, among the correspondence Kurt received and kept were letters from a friendly Nazi, H. DeLaporte, who kept Kurt apprised of what was happening in Wetzlar.

Meanwhile, it didn’t take long for Kurt to settle into his job of mounting and repairing cameras, and immediately he was working on ways to bring his younger brother and sister to the United States. There were a number of obstacles to surmount. First of all, their father didn’t want them to leave Germany. Their mother, however, was extremely anxious. She wondered if she were going crazy, if she was the only one who could see that things were not going to get any better in Germany. She begged her husband to let the twins leave the country.

In the U.S., Kurt and his older brother Herman were doing all they could to help the family back in Germany: sending them food and money, plowing through the paperwork to get the proper guarantees for their younger siblings. Meanwhile, they were hearing increasingly bad news from home. Their father, Georg, wrote on May 10, 1938: “The last few weeks brought us here all kinds of unpleasantness. It seems as if Frankfurt had the ambition to take the lead (in applying the anti-Jewish laws), and although we have not been personally hurt by it yet, the fate of our friends and acquaintances does not leave us indifferent. This takes a serious toll on the nerves, especially since something much worse seems to be building up than what is already there.”

Finally in October 1938, the affidavits for the children came through, with the summons to appear before the US consulate in Stuttgart to follow within six months. Meanwhile the children were practicing their trade skills and preparing for their new lives in America. Both studied English, while Ursula trained for tailoring, and Gerd, following in his brother’s footsteps, studied photography. “Gerd is learning a lot in his profession. He made a number of very nice room-photographs at home that got an A in the opinion of his very critical boss,” wrote the parents to America.

At the same time, Kurt borrowed $1500 in a private loan from a Mr. Seligmann from Wetzlar to have proof of a good bank account in order to be a guarantor for his parents’ entry visas into the U.S.

In early November, their mother Rosel was in and out of the hospital. Days later, on Nov. 9-10, the government-organized pogrom, known as Kristallnacht, struck German Jews. Thousands of synagogues, Jewish-owned business and homes were destroyed. More than 26,000 male Jews were rounded up and put in the concentration camps of Dachau, Buchenwald and Sachsenhausen. At least 91 Jews were killed. One of the subsequent cables sent to America in cryptic words - informing Kurt and Herman that their father had temporarily been sent to Buchenwald, but released because of his age - was sent directly to Kurt at the Ernst Leitz Co. on Fifth Avenue in New York.

A letter-writing campaign to cousins in Brighton, England, about ways to get the twins out of Germany, quickened its pace. Money was sent from America to the Midland Bank Ltd. in Brighton, for the guarantees. The Refugee Relief Council in Brighton and the Committee for the Care of Children from Germany, on Bloomsbury Street in London, helped orchestrate the process. All to get the 17-year-olds from Germany to the UK, where they would stay until they could travel on to their older brothers in the US. The plan was for the children to get to the UK first, followed by their parents.

Then, in March 1939, Rosel, the children’s mother, died. She didn’t live to see her youngest children safe out of Germany. With the weight of the responsibility for the children on his head, Georg panicked. As their Brighton cousin, Charlotte Tuchmann, wrote to the German Jewish Aid Committee March 30, 1939, about the twins: “Their father has been in a concentration camp and though released, seems to fear that he may be detained again. The mother of the children died a fortnight ago, her sudden death at the age of 43 being more or less the outcome of the continuous nervous torture under which these people are living. Should the father be taken to a camp again, the children would be left completely helpless. Besides, they are both of the age where they may be put in a labour-camp and once there, there would be no question of getting them out for a long time.” She further explains that the children have low US quota numbers that could be called at any time, but meanwhile she begged that the children be allowed “to spend these last dangerous months here in safety.”

That July, the twins arrived in London on one of the “kindertransports.” In Gerd’s first letter to Kurt after escaping Germany, he wrote: “At half past five, we arrived at Emmerich on the border. My suitcase with the photographic equipment was, of course, opened and I had the fright of my life. But after seeing the detailed lists of all my things, he did not say anything more.” Camera equipment, of course, could be taken out of Germany, whereas hard currency could not. Not long after the twins arrived in England, one of Kurt’s letters back to his family noted that Anton Baumannof, 38, fell to his death as he was taking pictures. Kurt called the accident a “great loss” to the company.

After the children had been in England a number of months, waiting for their quota numbers to be called, they finally sailed for the US the following March. Just a few months after the twins were reunited their older brothers in California, Gerd, who had childhood diabetes, hanged himself. His twin sister Ursula discovered his body. During the times when Kurt was forced to deal with his mother’s, then brother’s, deaths, his Leica work was his refuge and solace.

Tragedy upon tragedy continued to fall on Kurt’s family. His father was deported to a concentration camp in 1941, the same year Kurt decided to enlist in the US army. The last anyone heard from Georg was August 1942. Kurt’s aunt and her two young daughters were deported and (later) declared dead in September 1942.

Kurt was inducted into the US Army in April 1943, after his company had tried to defer his draft classification because of his “special” factory training. A year later, he was killed in action in the Mediterranean Sea. Today his sister Ursula is nearing her 80th birthday. All of Kurt’s relatives who remained in Germany were killed in the Holocaust. The cousins who left for Palestine have since died as well, although their descendants are still alive. What remains is Kurt’s and their story, carefully crafted through sometimes-daily letters, often carbon-copied and providently protected, along with hundreds of documents, and the photographic legacy of a young Leitz employee.

In subsequent articles, we will learn exactly how Leitz managed to save its Jewish employees, how its operations served both the US Army as well as the Luftwahfe, how the US operation tried to get replacement parts from Germany, and more about Kurt’s actual work for Leitz as well as his response when the New York police discovered the perpetrator of an amazing theft of camera equipment.